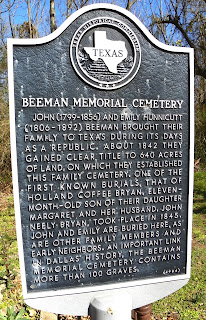

This is a land grant born from the heavy cost of a revolutionary war to gain independence from a tyrannical despotic regime. A great American from the State of Tennessee paid the ultimate price to have his name attached to the land here. His sacrifice forever consecrated this acreage of land with his family name. A Congressman, frontiersman and volunteer in the Army of The Republic of Texas who gave his life for a cause greater than his own on the morning of March 6, 1836 inside the walls of The Alamo. His name is known to every Native Texan ever to step foot in a Texas public school. Crockett. David "Davy" Crockett.

The 400 acre parcel of Great Trinity Forest that sits just west of the Trinity River Audubon Center was granted to Crockett by the Texas Government and Nacogdoches County for enlistment in the Army of the Republic of Texas. His wife, by then made a widow by the Battle of the Alamo, was given deed to the land. It still carries her name today, Elizabeth Crockett.

![]() |

| Sam Street's 1900 Map of Dallas showing the Crockett Headright on the Trinity River in what is now called the Great Trinity Forest, Dallas, Texas. |

On January 14, 1836, Crockett and 65 other men signed an oath before Judge John Forbes to the Provisional Government of Texas for six months: "I have taken the oath of government and have enrolled my name as a volunteer and will set out for the Rio Grande in a few days with the volunteers from the United States." Davy Crockett's military service entitled him to a "Labor and a League" of land here in Texas. A labor roughly equals a couple hundred acres of prime riparian land and a league is a little over 4400 acres that was out and away from a river.

![]() |

| Red-Tailed Hawk at the Audubon Center |

To qualify for a first class headright, the applicant was required to take the following oath: "I do solemnly swear, that I was a resident citizen of Texas at the date of the Declaration of Independence, that I did not leave the country during the campaigns of the Spring of 1836, to avoid a participation in the struggle, that I did not refuse to participate In the war, and that I did not aid or assist the enemy, that I have not previously received a title to any quantum of land, and that I conceive myself justly entitled, under the Constitution and Laws to the quantity of land for which I now apply."

That Crockett land for the most part looks the same today as when the people of the Republic granted the land to Crockett's widow. Deep old growth woods of majestic hardwoods, dense thickets of vines and underbrush that are the incubator for wildlife. Crockett's widow ultimately decided to live on another piece of her husband's granted lands near Acton but the name CROCKETT will forever stare back at whoever holds deed to the land.

To those unfamiliar with the Great Trinity Forest, a romantic tale like that is how they picture one of the largest urban parklands in the United States. Big, open and green. I wish all of the land down there was like that. It's not. It has been dumped on and destroyed upon for decades. Some of the worst damage has been inflicted just within the last five years.

![]() |

| A sea of wildflowers on the Pemberton Back Forty near White Rock Creek |

The millions of dollars in remediation involved in fixing the problems here threaten to damage the fragile life that still exists. New construction threatens places of epic importance to all Texans, the Audubon Center, a natural spring called Big Spring, Native American sites and a unique riparian watershed that is home to thousands of animals.

The problems here, the unresolved issues, the sheer magnitude of what is at stake for the future of the Great Trinity Forest needs a larger audience. I cannot do it myself.

My eyes get glazed over reading all this stuff. I hate talking about it. Takes all the fun out of coming down to the Trinity River to be honest. My introduction to this part of the Great Trinity Forest began with the Texas Horse Park. The first executive director of the Texas Horse Park invited me for breakfast at Kuby's early one morning and hashed out introductions with many of whom so many of you have learned about through this blog. So many good things have come from that.

What started some years ago with me blindly wandering around on a mountain bike by myself now has now turned into a large and well respected group of people dedicated to preserving and protecting the unique nature and sites down on the Trinity. There is no name, no organization, no leader. Just a large and ever expanding group of like minded folks from very diverse professional backgrounds. Biologists, foresters, chemists, engineers, attorneys, doctors, educators, I think even a yankee and two Oklahomans snuck in to boot. Decades upon decades of experience they each bring to this issue. Measured and methodical in their approach. Far smarter than I, it's a pleasure to spend time with them on these salons in the wild.

The most well respected names in Texas environmental causes have visited this spring and early summer. It has been an honor to meet so many of them. They have taken away a deeper understanding of the place, documented it with careful field notes and have each brought an important pair of new eyes to watch what happens next. They are accomplished authors, public speakers, journalists and lecturers. Well versed in making their voice heard if needed.

Often on these visits to the woods, standing shoulder to shoulder will be the grandson descendants of the Beeman and Pemberton families, representing 172 years of continuous family land ownership in the Great Trinity Forest. They know what's right for the future here in these woods. The city needs to embrace them and their family legacy. A century from now it will be looked upon as preserving the richest family story in Dallas County. Historian and Beeman, MC Toyer and Billy Ray Pemberton are the family Patriarchs of the Trinity. They hold the torch. A big bright torch with a flame so high you cannot see the top. If the city wants to continue the rich history down here and carry the torch themselves, they need to wrap their arms around the brotherhood of these men. They both want to help but cannot find the right people to engage with inside city hall. It's the city that needs the guiding light and the help.

A Condensed Primer On What's Going On --

![]() |

| Turtle in Big Spring |

It has taken a bunch of folks months to get all the facts to assemble a somewhat complete picture. Still foggy on where all the development is headed and who is really behind the push to build all this. Is it an Olympic Bid? Real estate developers wanting a new Las Colinas? Who? Don't ask me.

The two links below distill the raw data into two condensed executive summaries. Click on them to download the pdfs. The underlying questions are ones for which I do not have an answer. The links explain much of how it happened and what will happen in regards to cleanup:

Dang, the Horse Park land is messed up, how are they gonna fix that, who the hell screwed that place up?If you are a resident of the Pemberton Hill neighborhood and on well water the above link is a must read.

How they are gonna fix the future golf course is it gonna screw over the Audubon Center?Read on below for a further explanation or even better go straight to the source:

http://savepembertonsbigspring.wordpress.com/Compiled by Hal and Ted Barker, the website has links to raw data that can take days to read. Much of the information was aggregated by

Open Record Request some of which required a Texas Attorney General opinion to obtain.

It's time for the City of Dallas to get on the ball with all this.

The Old Ghosts of a Time Long Since Passed![]() |

| John Beeman's Republic of Texas medallion on White Rock Creek |

Some oldtime ghosts hide out down here. They manifest themselves in the slightest of ways. An old fencepost that contained a herd of dairy cows. An old foundation for a barn burned half a century ago. An old plow worn to nothing by the ravages of a hard scrabble sod it once busted one hundred years prior. Discarded and left to rot away in whatever half-life timeframe it takes water, sun or rust to vanish it from view. The time when those tools were sharp, well-oiled and carefully fitted represented a golden age of sorts for the Trinity River Bottom in Dallas County.

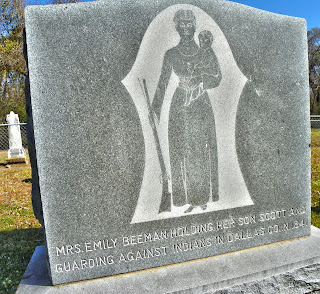

![]() |

| Emily Beeman; Frontier Mother, Frontier Defender |

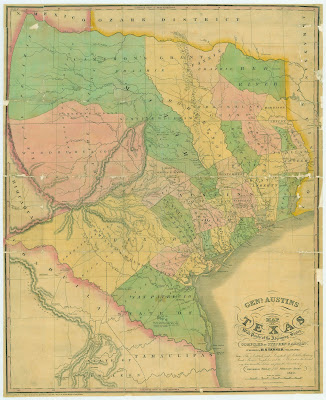

![]() |

| Beeman Cemetery |

![]() |

| Warren Ferris; Surveyor, Indian Fighter, Explorer |

The only permanent markers that stand to the men and women who first settled here lie in long forgotten areas of town. In a graveyard or two, their headstones recall a time where the people were undemanding and far between.

Like the first true family to permanently settle Dallas, the Beemans. The women of the family, like Emily Beeman, posed with child in one arm and a rifle in the other.

The stories of mountain man surveyor and author Warren Ferris. A man who mapped the unmapped on the heels of the Lewis and Clark Expedition across Wyoming, Montana and Idaho. Explorer of Yellowstone and the man who penned Life in the Rocky Mountains: A Diary of Wanderings on the Sources of the Rivers Missouri, Columbia, and Colorado. He was the true to life Robert Redford's Jeremiah Johnson. Kevin Costner's John Dunbar. The real McCoy. In the 1830s Ferris moved to the infant Republic of Texas where he became the official surveyor for Nacogdoches County. In 1839 Ferris surveyed at the Three Forks of the Trinity River deciding the lines and direction of streets for today's Dallas County. Ferris entered and surveyed this land prior to John Neely Bryan, the widely accepted founder of Dallas. Ferris exploits with the Indians who roamed what is now Dallas rival that of his encounters with the Rocky Mountain tribes. A rich legacy left to fade away. ![]() Some hope that whatever history happened down here one hundred or a thousand or ten thousand years ago is forgotten just long enough to physically erase whatever still remains. Vanished for good.

There is money to be made, you see. Rezoned for 200 foot tall hotels, restaurants and bars the city has renamed the Great Trinity Forest Z123-195. A potential playground for those with the money and connections. A warning sign.

|

|

Pre-Historic Sites ![]() |

| Forrest Kirkland |

December 29, 1940 was a cold bright day in Dallas. One where the late fall frosts had worked their magic on the last summer's batch of weeds and undergrowth making for a perfect day to explore the Trinity River. Out that day was Forrest Kirkland, founder of the Dallas Archeological Society and foremost expert on Texas Native American rock art.

![]()

On the same day when the Luftwaffe was unleashing upon London one of the heaviest firebombing raids of the Battle Of Britain, Forrest Kirkland was sketching and documenting a large Native American Site just South of the Pemberton Farm and Big Spring. Given the designation DL73, he documented a large and expansive Native American occupation area some 600 yards in length running north to south across what some day might become the Texas Horse Park. His field notes discuss the large amount of bird points, arrowheads and even grind stones found at the location in the vicinity of a small unnamed tributary to the Trinity River.

![]() |

| Forrest Kirkland's report of DL73; photo credit Dr Tim Dalbey |

Forrest Kirkland established himself as one of the leading researchers on Texas Native American Rock Art. During the work week he was an illustrator and designer of print media catalogs and advertisements. His design company was well respected and the industry leader of it's day. Living in Dallas, his weekends were often filled with exploration and fieldwork in the Dallas metropolitan area. In the 1930s and early 1940s much of Dallas County was still rural in nature, affording him great expanses of open terrain in which to work.

His prolific study of White Rock Creek yielded numerous archeological sites from the source tributaries in Collin County all the way to the mouth of White Rock where it enters the Trinity River.

Protecting Big Spring and Native American SitesOn the surface, little has changed in the way much of the land looked in 1940 when Forrest Kirkland was taking his field notes, searching the unnamed tributaries and briar laden undergrowth for a long lost Indian civilization. That site was largely spared the ravages in the decades to come. It's still there but for how long.

Citizen science has always played a vital role in the discovery, conservation and preservation of unique historical sites in Texas. Without the scientific observations of private citizens much of the invaluable history of Dallas would be lost or never found to begin with.

![]() |

| Native American hammerstones, raw unfinished rocks and unique hematite worked pieces found over the decades at Big Spring |

![]() |

| Rich Grayson(left) and Dr Tim Dalbey(right) |

The work that Forrest Kirkland began with survey forms and sketches continues to this day. It's thankless work that requires careful observation, scientific know-how and a grit to get a job done that no one else will.

There are some unsung heroes who have been at work doing this kind of thing for years down in the woods. Guys like Rich Grayson and Tim Dalbey, seen at left doing the monthly TCEQ and EPA certified water test on Big Spring in late June 2013.

Rich is the DFW Coordinator for the Texas Stream Team, a cooperative partnership between Texas State University, the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ), and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). His test criteria meets and exceeds federal, state and local standards. Carrying the identifier #80939, Big Spring is an official monitored site. In addition to coordinating water tests in the DFW area, Rich serves a webmaster for

Friends of the Brazos.

Geoarcheologist Tim Dalbey has been instrumental in keeping everyone honest(so far, fingers crossed) about DL72, the Big Spring archeology site that extends into the platted area of the Texas Horse Park at 811 Pemberton Hill Road. The 13th century pottery and beautiful ceremonial style arrowheads found here in early 2013 by the city contracted archeology company suggest something very special lies beneath the Horse Park. What it might be remains to be seen.

![]() |

| Sunset over the Trinity River Valley, Dallas, Texas June 2013 in the Pemberton Wildflower Meadow that serves as an important bio-buffer for Big Spring seen in the trees beyond. Pictured at left Rich Grayson, right Billy Ray Pemberton |

The real concern is that Big Spring is so special, so unique that if the site were ever compromised, ever built upon, ever fenced off that the damage could never be undone. The water is pure and cold. A solid 25 gallons a minute even in the heart of a Texas summer.

No politician or city official can take credit for any conservation effort here at Big Spring. The pristine pasture is a result of regular citizens rolling up their sleeves and taking a vested interest in the place. Lending a helping hand. The result is a slice of Old Texas. The Republic. The Lone Star. Smells like the country. Sounds of the city melt away. You know what that's about.

![]() |

| The ancient Bur Oak of Big Spring dwarfing Billy Ray Pemberton at left and Rich Grayson right, June 2013 |

![]() |

| Billy Ray Pemberton and his 133 year family legacy on the land here |

![]() |

| Billy Ray Pemberton; Modern Day White Rock Farmer |

The real star is the man responsible for watching over this land like an eagle. Billy Ray Pemberton. For decades he has been the silent watchman of this place, tending to the fields, the downed limbs and the occasional tire that floats by when the Trinity River floods. He alone is why this place is so special.

He and his wife Zada have fought harder for the land here than anyone who came before them. Deeply devoted to the teachings of The Bible and the land, they have developed a harmony here where their moral high ground values and solid work ethic inspire so many others to join their cause.

![]() |

| Big Spring at the Pemberton Farm |

![]()

A walk of this land as a whole, to view the entirety of such a place will only make you appreciate Big Spring more. It is literally the only place of it's kind.

Native Americans used the Spring on an extensive basis.Their tools and tool making pieces litter the ground here. Centuries worth. President Sam Houston slept here at Big Spring nearly 170 years ago with his entourage Treaty Party that made peace with the Indians of North Texas in 1843.

Mr Pemberton learned much about the land and farming, how to run a ranch by a man named Wallace Jenkins.

Wallace Jenkins 1930s-early 1960s![]() |

| Wallace Jenkins; 1950s Farmer, Rancher on his farm at 811 Pemberton Hill Road among his waist high oat crop |

Wallace Jenkins was a big man in Dallas County. A businessman from the oil fields and commercial farmer, he owned what is now called 811 Pemberton Hill Road and lands further to the south. He purchased what was then the Kirby Farm, an old farmstead that was in the Kirby Family. He bought it on the cheap, in the darkest days of the Great Depression when Texas farming and ranching were on the wane.

![]() |

| Pond B on the north end of DL73 built during the time Wallace Jenkins owned 811 Pemberton Hill |

With hundreds of acres under plow and hundreds of cattle grazing pastures his farm was one of the largest at the time in Dallas County. He served as a Dallas County Commissioner during the 1950s and as a close friend of Sam Rayburn, was instrumental in the building of reservoirs and flood control lakes in North Texas. During the 1950s, Dallas was in a decade's long drought, his efforts brought us the reliable water supply we now have today.

![]() |

| Wallace Jenkins service bay garages |

The Jenkins Farm must have been a sight to behold. Mr Pemberton worked there as a young boy in the 1940s tending to small chores around the ranch headquarters. Jenkins kept two Lincoln Zephyr automobiles on the ranch according to Mr Pemberton, that Jenkins would use to drive his property. Many of the Jenkins structures stood until 2012 when they were bulldozed.

The end of the Wallace Jenkins Farm era represents the end of anything good that ever happened here. All downhill from 1965 through 2013.

The Simpkins Tract -- Metropolitan Sand and Gravel --The Teamsters --The Syndicate

![]() |

| The Loop 12 Landfill about where the PGA Clubhouse will be built |

It was in July of 1965 that Jimmy Hoffa's attorney Morris Shenker acting on behalf of the Teamsters made a $1.4 million dollar loan from the Teamster pension fund to a St Louis based sand and gravel operation known as Metropolitan Sand and Gravel. A Missouri oilman named Joe Simpkins along with Morris Shenker fronted the deal and threw in $300,000 of their own money purchasing a total of 2800 acres of prime Trinity River frontage in Southern Dallas. Morris A Shenker, Farrell Kahn, Morris A Shenker jr, and Joe Simpkin were the principals. Thus the Simpkins Tract was born. So were a half century of problems that we live with to this day.

![]()

You might remember Morris. He's famous. Made famous(er) in the mid 1990s by Martin Scorsese's movie

Casino. Morris is portrayed in the movie by actor Richard Riehle as a "back east" attorney who receives a tongue lashed speech from Joe Pesci's character Nicky.

Shenker first came to national attention during the Kefauver Hearings in the early 1950s, in which he represented a number of underworld figures. From 1962 onward Shenker represented Jimmy Hoffa, and in 1966 became Hoffa's chief counsel. In 1970 a year-long Life Magazine investigative report accused him, as head of the St. Louis Commission on Crime and Law Enforcement, along with the city's mayor Alfonso J. Cervantes, of both having "personal ties to the underworld". The magazine alleged that Shenker controlled the massive $700 million Teamsters Union Pension Fund and its investments, most notably in Las Vegas but also in San Diego (through developer Louis Lesser), New York, Kansas City, and elsewhere. In the late 1960s, Morris Shenker bought an interest in the Dunes and became its Chairman of the Board. Because of his Teamsters connection, Shenker, who operated the Dunes Hotel and Casino in the 1970s, ran afoul of the Nevada Gaming Commission.

![]() |

| View of Downtown Dallas from Trinity River Golf site |

The Teamsters saw all the land down here as a future inland port and intermodal facility that would serve as a massive transportation hub for the ever growing and expanding sunbelt states of the Mid-West. They bought into the notion that the Trinity would become a navigable waterway from Fort Worth to the Gulf of Mexico and that levees would be extended as far south as present day Ferris to reclaim flood prone lands.

The Teamsters and their backers were always at odds with the city. When the Trinity River canal plans began to fizzle the investment group started facing political heat from the city wanting the land repurposed for a landfill. The group of investors looked at other uses for the land including a large mobile home trailer park, apartments and a new housing subdivision.

Metropolitan Sand and Gravel ran a gravel pit operation south of Elam Road from the mid 1960s to the mid 1970s. During this time they also ran a private landfill operation on a moderate scale.

In 1975, the City of Dallas under permit began a large landfill operation south of Elam Road and northwest of the present day Trinity River Audubon Center. They became known as the Elam and South Loop Landfills. As an interesting sidenote, originally one partner in the investment group defaulted on his loan regarding the land here. He used a 20 acre parcel of land as collateral near Downtown Dallas. The Teamsters took possession of the land with the default of the loan. That land was later sold to Ray Hunt who developed it into Reunion Arena and Reunion Tower.

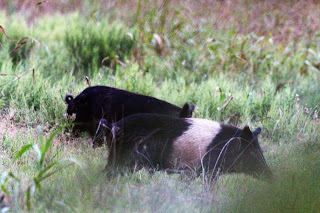

The Landfill And How The City Got the Land ![]() |

| Feral pig damage that unearthed a section of the buried Elam landfill |

The official landfills down here were in operation from 1975-1983. In the late 50s and early 60s there were some unofficial landfill activities of unknown origin west of the Elam Landfill and south of Elam road. These unofficial landfill locations have shown in the official sampling documentation to be a major point of concern.

![]() |

| The Burrescia land at 5950 Elam Road just east of the old Elam Landfill |

With the landfill closures in 1983, the capping and monitoring of the landfills began. A layer of dirt and limestone based crushed rock was placed over the top providing a thin veneer "cap" of the landfill. Over the next two decades periodic testing was completed on the landfill with installation of further monitoring wells, investigations into toxic materials dumped inside the landfills, methane etc.

![]() |

| 5950 Elam Road, former home of Let's Cowboy Up a Non-Profit grass roots community horsemanship group |

In 2008 the City of Dallas acquired the land in an unorthodox method. Hard to explain but it involved a complex set of lawsuits and land unrelated to the Great Trinity Forest. The Dallas Business Journal has a great article about it from 2008 and can be found on their website

Dallas Makes Trinity Forest Grab by Bill Hethcock. That story continues to this day

Dallas appeals court vacates city's $750k jury award.

When the city bought the landfill, they inherited not only a landfill with underlying problems but a tenant running a slaughterhouse operation at 811 Pemberton Hill Road. The cleanup and long term legacy of fixing issues that stem from that are ones that will be shouldered on the backs of taxpayers for years to come. The TCEQ found the City of Dallas landfill in violation back in 2008 and thus set in motion a mandatory/voluntary cleanup.

![]() |

| Animal Carcass Pit at 811 Pemberton Hill Road |

The slaughterhouse cleanup, well, that's a different story. Sitting on the footprint of the planned Texas Horse Park, every shovel full of dirt has a surprise. Surprise means expensive. Shame on somebody. It still baffles me how this was allowed to happen.

![]() |

| White Indian Paintbrush a rare sight |

Cleaning It Up![]() |

| Tire Dump Southwest of Pond B |

![]() |

| Terracon Map |

Earlier in the post I linked to a pair of executive summaries that serve as a good overview of the task ahead

Dang, the Horse Park land is messed up, how are they gonna fix that, who the hell screwed that place up?How they are gonna fix the future golf course is it gonna screw over the Audubon Center?The testing done to determine the pollution and toxicity of the soil, groundwater and surface conditions is very detailed. Broken down by location and chemical it serves as an excellent guide to where the problem areas are.

![]() |

| Terracon drilling equipment in Big Spring Pasture winter 2013 |

The links below will take you to the Barker Brothers

Save Pemberton's Big Spring website and are in pdf form:

Site Plan MapProposed VCP Area MapSite Plan and Sampling LocationsPrior InvestigationsSoil Analytical Results ASoil Analytical Results BGroundwater Analytical ResultsSurface Water and Analytical ResultsIn order to make heads and tails of most of it I have amended a few maps to show locations of importance to many reading this in three sections. The

north section that focuses on Big Spring and the future Texas Horse Park. A

central section that has focuses on contaminated ponds and seeps that flow directly into the Trinity River. The last but not least is the

south section with the vital bird ponds that are so important to the Trinity River Audubon Center.

North Section -- Horse ParkIn red are areas of interest that are hard to spot on the Terracon Maps or are unlabeled. Of note is the Polynuclear Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAH PCLE Contamination Zone), see below. Polynuclear Aromatic Hydrocarbons are cancer causing substances that can be a root host of environmental damage and illnesses in humans.

![]() |

| PAH PCLE zone and mapped areas of nitrate contamination at the platted Horse Park site at 811 Pemberton Hill Road |

The cleanup in this area will require 2000-3000 cubic yards of contaminated soil to be removed. Huge cleanup effort and one that was unexpected. Where the money will come from to clean that up is a question that has yet to manifest itself with an answer.

![]() |

| Damaged area where weeds will not even grow |

Most PAHs in the environment are from incomplete burning of carbon-containing materials like oil, wood, garbage or coal. Many useful products such as mothballs, blacktop, and creosote wood preservatives contain PAHs.

The carcinogenicity of certain PAHs is well established in laboratory animals. Researchers have reported increased incidences of skin, lung, bladder, liver, and stomach cancers, as well as injection-site sarcomas, in animals. PAHs can also be directly genotoxic, meaning that the chemicals themselves or their breakdown products can directly interact with genes and cause damage to DNA. 2000-3000 cubic yards. All the dirt needs to be removed down to the bedrock.

![]() |

April 2013 aerial view of contamination area, foreground right(looking south from the Big Spring Pasture)

|

![]() |

| Texas Horse Park overlay showing building footprint over a portion of the contamination zone (looking south from the Big Spring Pasture) |

This damage could have an immense detrimental impact to DL72, a Native American site that sits directly to the east of the PAH PCLE zone. For sure the Native American site here is one of the single most important archeological sites in Dallas County. Frowns abound when those inside city hall discount the evidence of such.

![]() |

| DL72 Native American artifacts credit: Tim Dalbey |

The archeology site here extends north to south across the remnants of an old outcropped terrace that the Native Americans here used as a stone age hardware store for finding suitable rocks for weapons and tools. Throw in the native bois 'd arc and honey locust trees that grow here and you have the makings of a bow and arrow factory. Whether or not the city will preserve the site or ultimately destroy it is an unanswered question. Wish I knew.

Fire up Google Earth and enter the KMZ file located here

Texas Horse Park Overlay to get a better look. Use Google Earth's fantastic History Tool to see historical imagery of the site. One will quickly see that this dumping unfortunately occurred rather recently.

![]() |

| Aerial overlay showing yellow boxed PAH PCLE zone credit: MC Toyer |

![]() |

| Contamination and monitoring overlay at 811 Pemberton Hill |

![]() |

| Horse Park Overlay |

![]() |

| Pond B |

According to construction documents and the contractors RFP, drainage for the Texas Horse Park and the many of the barns, arenas and stalls will drain into this "Pond B" area. Traditionally called Jenkins Pond this picturesque pond is partially fed by what is most likely an underground aquifer spring that sits at the same elevation as Big Spring further to the north. Beyond to the west is an environmentally sensitive area of beaver ponds, river otter and mink habitat.

![]() |

| The expansive former Animal Farm/Slaughter facility at 811 Pemberton Hill Road |

Contamination in this area is limited to an area that once housed a City of Dallas tenant running a slaughterhouse operation. Hard to figure out where so much of the debris and chemical contamination came from including large amounts of dumped animal fat in the woods. Lots of burned areas and burned pit material that suggests open pit trash fires. Broken glass, tile, asbestos and materials of unknown origin cover the site.

The worry to so many is that the carcinogens and other materials will enter the perched aquifer that runs the length of the escarpment. It would prove impossible to undo damage to the aquifer, a vital water supply that many neighbors still rely on for a water supply. This is a problem that needs be daylighted in the community as it could effect the well being of humans, pets and their livestock.

Central Section --

AT&T Trail and pollution entering directly into the Trinity RiverI have highlighted some areas of note in the Central Section. The barren area north of Loop 12 will be the 9 hole Golf Course and First Tee organization's HQ.

If you refer to the Terracon Maps linked earlier in the post, Pond J and the Seeps are of particular notes of contamination. High levels of thallium, lead, barium and other chemicals that are hazardous to man and beast alike. The area saw some pre-sanitary landfill dumping in the 1950s and early 1960s. The refuse leaches chemicals into the water there and directly enters the Trinity River unabated.

![]() |

| Limestone Seeps as seen from mid-stream in the Trinity River. Notice the concrete pipe in the far background. That pipe leads up to the Pond J area of concern, February 2013 |

![]() |

| Limestone seeps upstream of Loop 12, a popular fishing area for South Dallas residents, from February 2013 |

![]() |

| Rare Box Turtle on the Simpkins Tract |

This area is where the 80-100 million year old limestone of a long ago sea bed meets the 100,000 year old pleistocene gravels of the Trinity Sands. Filtering down through all that old gravel and squeezing horizontally along the upper surface of that limestone is the groundwater aquifer that provides so many vital water in this part of Dallas. Where the outcrop meets the Trinity, the water seeps out of the cracks and crevices. The last 1/4 mile of it's trip, the water picks up a host of contaminants detailed in the Terracon maps. It's a shame because so many families now fish on the opposing bank here and down at the Loop 12 Boat Ramp downstream. It's concentrated pollution here. Thallium is known to cause birth defects and the seeps give the Trinity a toxic cocktail of it here at this spot.

![]() |

| Pave The Trinity Trail Plan source: City of Dallas |

The proposed AT&T Trail might one day run right through this contamination area. The city contractor notes that extensive remediation will need to be done so that human recreation can happen here. Just the idea of the AT&T Trail is a poorly thought through premise. This area will only complicate matters for an proposed trail that is not welcomed by so many users down here.

South Section--The Golf Course and the special ponds![]()

According to the contractor documents, the southern portion of the landfill cap here is failing. The remediation plan is one of heavy construction in this area, one that will most likely have a direct impact on some very important ponds. Pond M, Pond Q and Pond T.

Pond T and the unnamed small pond directly to the west of the Audubon Center serve as the lifeblood of fin and feather for the facility. It's a series of ponds where the shallow water allows for wading birds, otters and other wildlife a secluded retreat where they can feed, breed and raise young. One of the single most important ponds in Dallas County.

There is contamination around it that will need to be addressed. Whether or not the dynamics of the pond are detrimentally harmed by this construction is unknown.

Send an email to the Golf Course designersIf you are a patron and fan of the Audubon Center(awesome place) take the time to email the design firm for the Trinity Forest Golf Course, Coore and Crenshaw

http://www.coorecrenshaw.com/. They are still designing the course and the elements to incorporate it into the environment down on the river. Let them know what you like about the Audubon Center and let them know how concerned you are about the Golf Course moving in next door. The golf course can be built in a manner that is wildlife friendly and let them know that you'd like to see it built that way.

![]()

The city is essentially privatizing a huge chunk of what the still refer to as the Great Trinity Forest. A giant donut hole in what the city always advertised as the largest urban park in the United States. No more.With a slight of hand change in zoning, the parkland and woods we all know as a urban refuge will soon become a private enclave for the wealthy.

The zoning in certain areas, namely the Solano Soccer Club allow for a large building, maybe even a hotel the size of those seen in Las Colinas. The history and the sites which I have detailed here will most certainly be impacted and many will be lost forever. The Native American sites, the wildlife and great Trinity River itself will vanish as we know it.

![]()

Some of us are arriving a little late to the awareness to the swindling the land got down here. It will be hard to finger blame on someone for it as a result. After all, our city hall forefathers spent the better part of the last century trying the best they could to kill off the natural world down here and they damn near accomplished it.

Seems that going through the documents about all the damage that surely occurred after the City of Dallas 2008 purchase that we as citizens of Dallas seem to have been occupying ourselves with finishing the job those so long ago started. Shame on us. We should have been watching....we are now.

Surprising to see more and more people out at these things. Just a couple years ago I'm certain that I was the only one out there on the levee photographing the moon. On this particular night there were about one hundred. Some here on their own, some in pairs, some in groups.

Surprising to see more and more people out at these things. Just a couple years ago I'm certain that I was the only one out there on the levee photographing the moon. On this particular night there were about one hundred. Some here on their own, some in pairs, some in groups.