![]() |

| The mighty Lock and Dam #2 on the Trinity River in Dallas County's Goat Island Preserve |

The usually placid and calm river grumbles and roars here in protest. A place whose concrete buttresses stand as a monument to a grand idea and best laid intentions of past generations run afoul. An aspirational dream of transforming the Trinity River from a naturally coursed stream into a boondoggle of an idea that never got off the ground. The river, the longest wholly inside the State of Texas had other plans. No public place on the river can serve as a more telling landscape to witness this than at Lock and Dam #2 at Goat Island Preserve.

Location:

2800 Post Oak Road

Trailhead at 2800 Post Oak Road Wilmer, TexasFrom Dallas take I-45 south to the Fulghum Road exit, head east where it eventually turns into Post Oak. Trailhead is easy to spot at one of the 90 degree bends in the road. New trailhead parking lot and sign note the entrance. One or two parking spots exist at the Beltline Road bridge but might interfere with ongoing construction activities if you park for extended periods.

Contact:http://www.dorba.org/trail.php?t=41 goatisland@dorba.orghttps://www.facebook.com/pages/Goat-Island-Preserve/523646911091310Goat Island Trails:Goat Island Preserve features two cutoff meanders that create islands in the river channel when the water is high. On the west bank of the river a large 1910-1920 era levee exists that runs from Post Oak to Beltline Road. As of this writing in November 2014, logging work is ongoing along the levee to clear trees. Borrow pits rest on either side and a lower dirt road trail runs between the levee and the river. Towering oaks and pecans are prominent here among succession forest. Lock and Dam #2 sits on the Trinity River just upstream of the Beltline Road bridge.

Trail Map![]() |

| Blue and Red marked lines are old ranch roads. The smaller yellow lines are trails currently built or are under construction. |

The locals call it Goat Island. Outsiders don't even know it exists. One man (you can help too) looks to change that obscurity into a well trodden path for hikers and mountain bikers at one of the best wilderness areas in Dallas County. He is Goat Island's Trail Steward and volunteer Joe Johnson.

![]() |

| Trail builder and trail steward Joe Johnson explaining to Master Naturalist Bill Holston how he worked some overlook sites into his trail designs at Goat Island |

Joe is nearly a one man show with the miles of smiles he is building on the west bank of the Trinity River. With the blessings of Dallas County Open Space Program and the Dallas Off Road Bicycle Association DORBA his mileage constructed increases monthly. It is from Beltline Road that his trails start a series of ever meandering loops and views of the Trinity River.

![]()

Joe Johnson's carefully planned loops work across old roadbeds that run parallel to the Trinity River. His trail loops radiate out from those established old farm roads built many decades ago when this was a working farm.

The double tracked trail into the preserve on either end follows the old farm road that had pig pens and barns on the north side of the preserve during the Little Oaks Farm era. Some faint traces of the old farm can still be seen if you look closely through the brush.

![]()

Old fence lines, some old gates and detritus from the old ranch are still visible. The old road to the north end sits on the Trinity Terrace sands, a slightly elevated piece of topography above the waxy clay of the river bottoms to the east.

This has always been a bottomland prone to immense flooding and the ruining of a cotton crop overnight. The wide swath of land here that Goat Island Preserve sits on is a collection of old farms that once fronted the river at the turn of the last century.

Clint Murchison Sr amassed a large holding of real estate down here in the many thousands of acres during the Great Depression from those old farms. The land holdings went by the name Bluebird Farm, the old signs in some of the pastures still note the name on ornate steel archways. Bluebird Farm was a land holding company that had roots in Dallas and back home to the Murchisons in Athens, Texas.

Little Oaks Farm and the namesake of Goat Island![]()

Murchison Sr owned the land here for decades using it has a cotton farm, cattle grazing operation and hunting lease. Murchison later sold a portion of the Bluebird Farm, 500 acres, land now called Goat Island Preserve to one of his own employees, Zedrick Moore.

![]() |

| Zedrick Moore tending to his exotic sheep |

Zedrick and Betty Moore's Little Oaks Farm was most likely the namesake for Goat Island. They bought the land here from the Murchisons shortly after their wedding. The husband Zedrick was an employee of Clint Murchison Sr. Their old ranch house still stands today, built by them in the early 1950s. It is directly across from the entrance to Goat Island Preserve and is surrounded on three sides by graveled mining pits.

It is from the north end of Goat Island Preserve that the old farm once stood. The northern end of the Trinity River Levee Improvement District #2 starts here too. Built and improved upon many times over the decades from 1917-1950. It's a simple piece of earthworks with dirt piled up from narrow trenched borrow pits on either side of the levee. Never designed to protect the farm fields from larger floods, the levees here were designed to protect property from seasonal and annual flood events.

![]() |

| A young stand of Ash trees at Goat Island Preserve |

Until recently, trees and vegetation were allowed to grow on the levees. Unclear as to whether or not the levees are still a functional facility for higher flooding events on the west side of the Trinity. I would believe they only offer marginal protection since they have not seen earthmoving improvements in so long.

The higher levee road(in red on the map) follows the top of an old levee road which runs the length of the preserve south to Beltline Road. The lower road which runs between borrow pits for the levee and the Trinity River is slightly to the east and meets the upper levee road at Beltline. A high water table in the area ensures that even during the driest of weather that the low road stays wet and muddy in spots.

Goat Island From Beltline Road ![]() |

| The pre-dawn light over the Beltline Road Bridge at the Trinity River |

![]() |

| Beltline Road Bridge |

This visit to Goat Island highlights Joe Johnson's work and he suggested starting at Beltline Road since the balance of trails constructed are on the south end of the preserve. From there he hiked us up through the loops of trails towards Lock and Dam #2 and then beyond to the islands where he has done some great work.

![]() |

| One of the lower trail loops that has views of the Trinity |

Best trail building practices call for following the natural terrain as practicable and staying a healthy distance from drop offs, streams or eroded areas. The Goat Island trails follow that edict. Lots of great flowing through the terrain with brief glimpses of the river.

The trails cross all kinds of wooded terrain that up until several months ago I would classify as a 9 out of 10 on a bushwhacking scale of difficulty to navigate. Heavy woods and underbrush coupled with head high greenbriar tangles.

The new trails make this largely a walk in the park, one that cub scouts could walk with parents.

An astute eye will notice some areas are recently forested over the last few decades with pioneer species of ash. As one walks further north you begin to encounter large galleries of cedar elm.

This is excellent mountain biking and hiking terrain. The trail alignment is such that one can really get in some quality miles here.

![]()

The cedar elm areas are truly spectacular in the autumn months as seen at right. The Virginia Wild Rye has turned a chesnut brown and gone to seed. The cedar elms have a hue of yellow to them.

These loops provide great insight into succession forest in the Dallas County Trinity River bottom. Very simple to understand how long it takes for the ecosystem here to repopulate after clearing.

The trails all eventually loop back to their original starting place or chain together towards Lock and Dam #2. The sound of the place draws you in towards it with each footstep.

Lock and Dam #2![]() |

| Joe Johnson at Lock and Dam #2 Dallas County Texas Goat Island Preserve Fall 2014 |

![]()

Trinity River Lock and Dam # 2 sits just upstream of Beltline Road. There are three locks on the Trinity River in Dallas County, #1 at McCommas Bluff, #2 at Parson's Slough/Goat Island and #4 near the mouth of Ten Mile Creek/ Riverbend Preserve.

All were built between 1910 and 1916.

The locks and dams in Dallas County never saw much river traffic. The idea to harness the power of the Trinity into a navigable water way was abandoned shortly after World War I in 1922.

Leaps in technology with long haul trucks and improvements in road and rail capacity sidelined the effort to move commerce via the river. Ideas at rebirthing the locks and dams on the Trinity came in the 1930s, 50s, 60s and 70s. These ideas were fanciful pursuits for the most part, grand visions with no science to support the effort.

Today we are left with the concrete foundations of the locks, twisted metal and fallen flood gates. Lock and Dam #2 is the most photogenic of the locks in Dallas County. The water literally roars here with long vista like approaches on either end. The other locks are constrained to some extent in the river channel and don't have wide eroded pools on the downstream side.

Each Boule Gate that was used in the lock was 24 feet high, 30 feet long and weighed 60,000 pounds. One gate formed half of a door, 1 door on the upstream end and 1 door on the downstream end completed the lock which was designed to raise and lower boat traffic.

Parson's SloughThe construction of Lock and Dam # 2 required the closing of a subchannel of the Trinity called Parson's Slough.

![]() |

| Sam Street's 1900 Map of Dallas County featuring Bois 'd Arc Island right of center |

The idea was to cutoff a 14 mile stretch of the traditional stream bed for a more westerly course putting all water in one channel of the Trinity. The old riverbed became known as Parson's Slough and the 22,000 acre area surrounded by the new and old river became Bois d' Arc Island.

![]() |

| Parson's name still lives on Bois d' Arc Island where Parson Slough Ranch commands a large acreage |

![]()

In 1911, the slough was permanently cutoff from the Trinity River near Goat Island Preserve. The same construction company that built Lock and Dam Number 2, built a concrete dam at the head of Parson's Slough where it meets the Trinity. Twenty feet high and two hundred feet wide, the goal was to permanently send the river down the new channel rather than risk a flood putting the river meander back in the old. Now buried under dozens of feet of silt, it cannot be seen from the west bank.

It sits near the outflow channel near the Southeast Wastewater Treatment Plant. Buried. Only during times of the very highest water flows would the dam become a spillway. Combined with some levee projects in the 1920s, this left Parson's Slough high and dry from the Trinity. The flood prone area now known as Bois d' Arc Island now serves as some of the very richest farmland in Dallas County. Much of which is owned by Trinity Industries for future gravel mining.

A Visit To The Biggest Black Willow You Ever Saw![]() |

| Probable State Champion Black Willow at Goat Island |

The new Goat Island trail system goes a number of places that really are in the boondocks of riverbottom. As the trail meanders up to the historic junction of where Parson's Slough and the Trinity once met, sits a meandering oxbow of sorts that hold what is most likely the Texas champion Black Willow.

![]() |

| Joe Johnson and the base of the old willow |

The current state champion Black Willow is at White Rock Lake Park and was lost in an October 2014 thunderstorm event that not only knocked down the 175 year old tree but left most of Dallas without power for days. Familiar with that tree that was lost, this Goat Island tree is much, much larger. It resides near the old cutoff, just right across the river from were Parson's Slough and the Trinity once forked.

Dallas County and North Texas really lacks giant trees. The visit here is worth it just to see this huge willow.

The old broken limbs of the tree that lay strewn about are larger than the main trunks of most mature willows. They are so large that the old knots collect water a gallon or more at a time like punch bowls.

I imagine at some point in the near future it can be officially measured to crown it the largest Black Willow in the State of Texas.

![]() |

| Multi trunked ash tree |

Moving north, the trees start to get older and the understory starts to reflect a mature hardwood forest. Beauty berry and rough leafed dogwood command the understory with larger species of oak and pecan beginning to show themselves in the distance.

![]() |

| Feral hog track in the mud at Goat Island |

Despite an exceptionally dry 2014 in North Texas, the lower road is still wet. The near permanent seeps here signify a shallow water table.

The DORBA mountain bike trail has been flagged through this area with work arounds for the muddiest of spots. Still in a flagged stage to a large degree, work is moving forward when conditions allow. The roads and dirt are rideable now, the pig paths and meandering coyote trails are too. Just don't expect a butter smooth and groomed ride.

The Trinity River has not experienced an overbanking flood event that would push water into this area since March 2012, almost two years ago. When that occurs, not only do the lower sections have standing water for long periods of time but the higher sections do as well.

Some areas that can become completely surrounded by water even during modest water levels in the river are the cutoff oxbow islands that give the preserve it's name.

Trails on the islands![]() |

| Crossing the first oxbow using a concrete access road for a sanitary sewer line |

Access to the islands can be made fairly easily using a pipeline right of way that runs roughly west to east across the levees and then transits the Trinity River to the wastewater treatment plant on the east bank of the Trinity. Some areas that can become completely surrounded by water even during modest water levels in the river are the cutoff oxbow islands that give the preserve it's name.

The point of reference to finding this spot is to locate the large lifting station structure on the west bank levee of the Trinity River and then follow the right of way.

Unless you want to swim or get hip deep in mud, the sewer line crossing at the westernmost oxbow is the only place to cross. Resembling a hill country low water crossing, the elevation is scarcely high enough to prevent wet feet in the driest of weather. This area will rapidly flood as it serves as a path of least resistance for the Trinity River.

![]() |

| Big gigantic trees as far as the eye can see |

It is here, beyond the reaches of where many would ever go, that the new trails provide access to places that were previously very hard to navigate. On the islands here one sees the richest collections of biodiverse plant species in the preserve. Towering oaks, elms, pecans and understory constituting many species.

The second island is just east of the first and is separated by a deep meander that lacks a concrete crossing. This is a very scenic spot, with large Bur Oak trees lining the meander on both sides. Many are quite large.

The river's shores around the islands here are dirt and steep, some twenty feet surmounted by cottonwood, willow and driftwood rafts. The hard limestone and sand beaches of the river sit on the opposing bank.

![]() |

| Sabal Minor palm trees growing on Goat Island |

The new trail also passes within about twenty feet of Sabal minor dwarf palmetto palms which are the native palm species to Dallas County. As I explore more and more remote places along the Trinity I encounter these plants in the oddest of places.

![]() |

| On Goat Island's new trail |

The trail out here on the island has the rolling topography of dips and twists that will please both hikers and cyclists. It needs more foot traffic to bed the trail down and some work to get it up to speed for mountain biking. The remote location of this place keeps traffic down which be nice but also detrimental to getting a trail bed established.

In winter the hike in is easy and a mountain bike would make quick work of the terrain with ease once the trail is bedded down. The larger Red Oaks, Pecans and Walnuts give way to more Ash and Bur Oak here as the terrain gets lower and more prone to sustained flooding events. The random white trunk or two of sycamores are down here as well.

Like most areas on the Trinity River, one does not encounter heavy briar thickets and privet until the last 30 yards around the riverbank. The waist high thickets are ones most generally avoid.

![]() |

| Huge trees with an open view hundreds of yards long |

Egress out of the area is simple using the lower or upper roads with many interconnecting animal trails between the two. Rumor has it at some point in the near future, the plan is to create a soft surface greenbelt trail along the levees that joins Goat Island Preserve and Riverbend Preserve to the south. Since this is unincorporated Dallas County and without a civic push it might be awhile before that becomes a reality.

If you live in Southern Dallas County or suburbs, Joe Johnson could use some buddies to get the trail in tip top shape. Use the links at the top of the post to contact him. This place has wonderful possibilities and limitless trail riding if some more traffic and elbow grease could get down there. It would make a great Eagle Scout, corporate giving day or church group project.

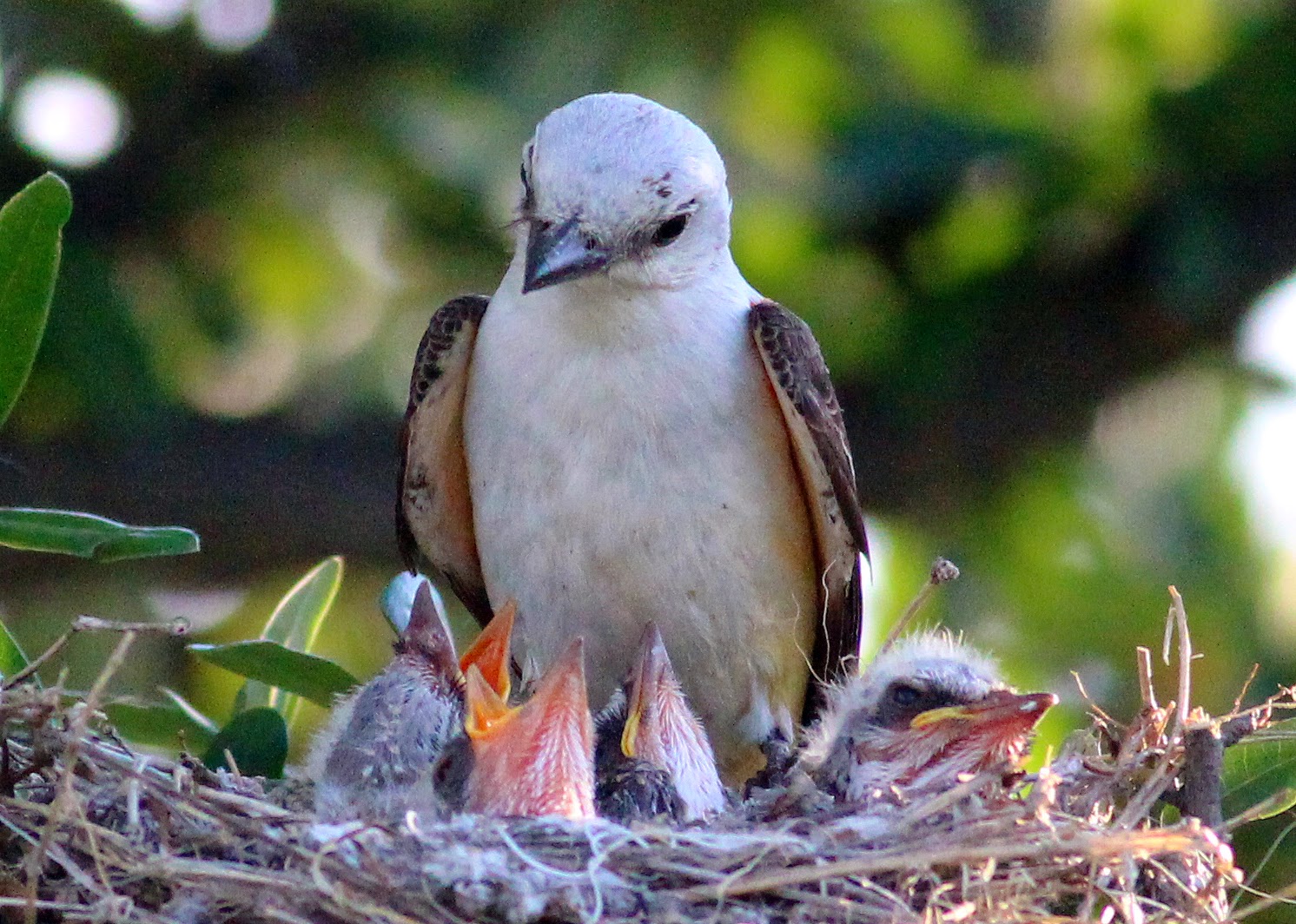

Three birds featured above, all wading birds of near similar size and height with all very different methods of catching prey.

Three birds featured above, all wading birds of near similar size and height with all very different methods of catching prey.

.jpg)